This is the fifth essay in a series by Peter VanderPoel, AIA, to help explain the fundamental principles and science of Passive House design. Read the first essay outlining the basics here, followed by the article on super insulation here, air barriers here, and thermal bridging here.

We now have Grandmother’s blanket around us, head-to-toe, all thermal bridging eliminated, and a windbreak so that we look an awful lot like a chrysalis. But something seems to be lacking…

Oxygen!

But punching a hole through the envelope ruins our carefully constructed, continuous thermal and air barriers.

In traditional construction, the method for introducing fresh air has been natural infiltration, i.e., leaky walls and windows. Now that we’ve eliminated the leaks with a continuous, uninterrupted air barrier, we need to introduce a purpose-built inlet straw (quick!).

The straw also allows us to exhale carbon dioxide from our lungs into the outdoors.

In the winter, though, that cold, fresh air coming in requires a lot of added heat energy to make it comfortable for the lungs, while at the same time, we’re exhausting stale air that sends a lot of heat energy outside. Your body has to expend energy to warm the incoming air, while the warmth from the outgoing air is lost to the ether.

In addition, our lungs are purposefully flexible to force air in and out. Buildings are rigid, however, and expelling exhaust air creates negative air pressure, which encourages hot/cold/humid outside air to come in through whatever tiny holes exist in the exterior envelope. Inhalation causes the opposite problem with pressurized air that the owner has paid to heat or cool, escaping out through the same, minuscule holes.

The fluctuating pressurization and depressurization that would result from a straw could be mitigated by providing two straws – one for fresh air, one for exhaust. This balanced exchange would eliminate pressure differences between inside and out, keeping the interior air where we want it.

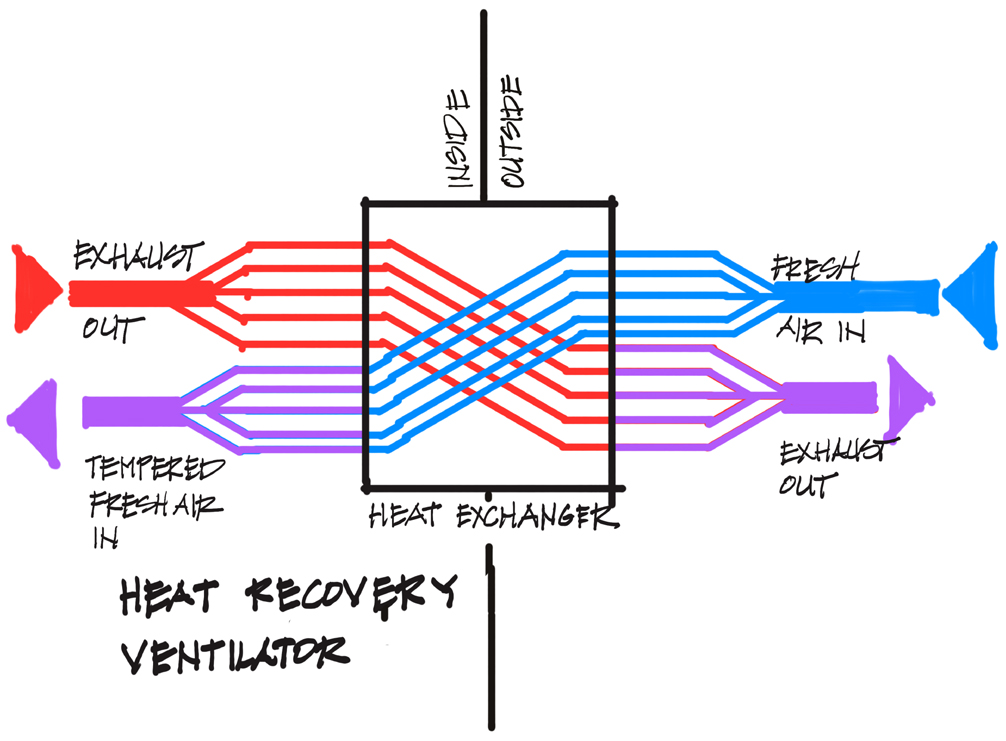

If our two-straw analogy now grows to a, say, 12-straw cylinder with 6 devoted to fresh air coming in and the other 6 to exhaust air going out, evenly mixed within the cylinder. The warm air being exhausted through the outgoing straws would warm the wall of the straw, which would conduct heat to the wall of the neighboring fresh air straw, warming the incoming fresh air. Now we can expend less energy from our body to warm the fresh air. This system, known as a Heat Recovery Ventilator (HRV), is very close to a literal series of tubes passing each other in a heat exchanger. The HRV is recommended for dry climates where humidity is not a concern.

The ERV (Energy Recovery Ventilator) is a similar product, but it can also recover humidity levels from outgoing air to reduce the energy used to adjust the humidity levels from the incoming air.

It was common in older, leakier houses to deliver fresh air and heat in the same tube, the ductwork that runs throughout the house. A furnace, likely located in the basement, would set something on fire: natural gas, oil, coal, etc., and then suck up ‘fresh’ air from the basement, available in copious amounts due to the lack of insulation and air sealing of the basement walls. A fan would then push the air across the flaming heat source (or refrigeration tubing) through the ducts to the various living spaces. Standard, too, was the practice of oversizing the equipment, just to be sure. In many parts of the country, hot summer days come with high humidity. Air conditioners can alleviate both problems, but the oversized systems would quickly provide cooler temperatures and switch off without addressing the high humidity, leaving discomfort and mold to grow on the walls and the inhabitants.

Now, fresh air requirements have remained the same, but with the substantial energy reduction from Passive House design, the heating and cooling requirements have decreased dramatically. The solution tends to be a separation of the two; a ventilation system introduces and distributes filtered, fresh air, and a separate system heats and cools the air already in the space.

Also falling by the wayside are HVAC systems using flaming combustibles to heat homes, which are losing market share to electric heat pumps. The principle of the heat pump is that it doesn’t create heat; it relocates it in a similar way you can move water from one place to another by using a sponge.

The weather service may tell us that it may be cold today, but it will be colder tomorrow: the difference is heat. Improved heat pump technologies are able to provide sufficient amounts of heat from cold air in most circumstances. If you go to the outdoor unit on a cold day, you’ll feel even colder air coming out of the unit after the warmth has been squeezed out of it, transferred to a fluid, piped into your house, with a breeze blown across the pipe.

Every building has to breathe. The problem with older houses is that they hyperventilate. Air moving in and out through holes and seams at the perimeter of the building allows energy and air quality to go out the window (figuratively and literally) in the process.

Next up: Tenet 5 – Can you see what’s coming next?

VanderPoel Architecture is located in Arlington, Virginia, and designs residential and light commercial projects throughout the Washington, DC metro area.

Peter VanderPoel AIA

703.725.4328

peter@pvanderpoel.com

Visit corcoranmce.com to search listings for sale in Washington, D.C., Maryland, Virginia, and West Virginia.

Don’t miss a post! Get the latest local guides and neighborhood news straight to your inbox!

Facebook

Facebook

X

X

Pinterest

Pinterest

Copy Link

Copy Link